The Ultimate Guide to CBG

Introduction

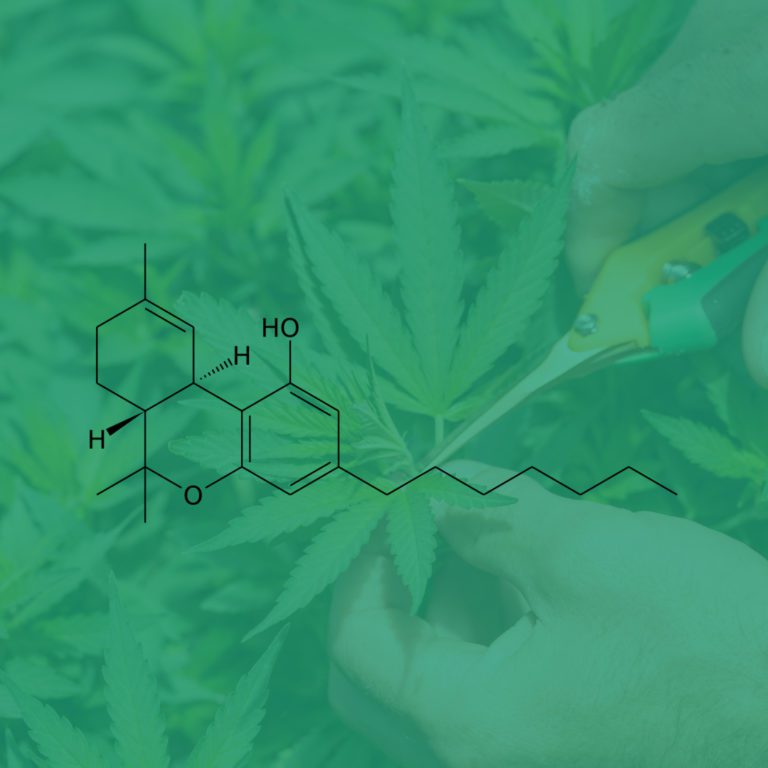

As cannabis research pushes forward, more cannabinoids are coming into focus. One of the most intriguing is Cannabigerol (CBG) — a compound earning increasing attention for its potential therapeutic benefits. Often called the “mother of all cannabinoids,” CBG serves as the chemical precursor to THC, CBD, and several other cannabinoids, placing it at the heart of cannabis science.

This article will explore what makes CBG unique, how it interacts with the human body, the research on its potential benefits, and the best ways to incorporate it into your flower.

What is CBG?

CBG, short for Cannabigerol, is a non-intoxicating cannabinoid found in the cannabis plant. Unlike THC, it doesn’t produce a psychoactive “high.” Instead, it offers a different array of potential therapeutic effects.

CBG exists in only small quantities in most mature cannabis plants — often less than 1% by weight — making it a relatively rare compound compared to THC or CBD.

CBG: The Mother Cannabinoid

During the early growth stages of cannabis, the plant produces large amounts of CBGA (Cannabigerolic acid). As the plant matures, enzymes convert CBGA into THCA (tetrahydrocannabinolic acid), CBDA (cannabidiolic acid), and CBCA (cannabichromenic acid). Through decarboxylation (heat exposure), these acids later become THC, CBD, and CBC.Only a small fraction of CBGA remains unconverted, which becomes CBG after heating. Because of this transformation role, CBG is often referred to as the “stem cell” or “parent” cannabinoid of cannabis.

II. The Science: How CBG Works in the Body

The Endocannabinoid System (ECS)

CBG interacts with the body’s endocannabinoid system (ECS), a complex cell-signaling network responsible for maintaining physiological balance. The ECS regulates functions such as mood, appetite, pain sensation, inflammation, and immune responses.

While THC binds primarily to CB1 receptors in the brain (causing psychoactive effects), CBG is believed to bind weakly to both CB1 and CB2 receptors, possibly acting as a mild agonist or even a modulator.This different binding pattern may explain why CBG does not produce intoxication, yet still influences processes like inflammation and pain. Research also suggests that CBG may inhibit the enzyme FAAH (fatty acid amide hydrolase), which breaks down the body’s own endocannabinoid anandamide. By slowing this breakdown, CBG could indirectly boost mood and stress resilience.

Potential Benefits of CBG

Important note: Most of what we know about CBG so far comes from early research in labs and animal studies. More high-quality human research is still needed to fully understand its effects.

1. Anti-Inflammatory Effects

CBG has shown promise in reducing inflammation. Animal studies suggest it may help with conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) by reducing nitric oxide production and oxidative stress in the gut.

2. Neuroprotective Properties

Preliminary studies indicate CBG might have neuroprotective effects. Research on models of Huntington’s disease found that CBG could protect neurons, reduce inflammation, and improve motor deficits.

3. Supporting Eye Health

CBG may help reduce intraocular pressure, making it of interest in potential treatments for glaucoma. Unlike THC, it does so without psychoactive effects, although much more study is required.

4. Antibacterial Activity

CBG has demonstrated strong antibacterial properties, particularly against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). This suggests future exploration of CBG in combating antibiotic-resistant infections.

5. Appetite Stimulation

Animal research also shows CBG might help stimulate appetite. In contrast to THC, which also increases appetite but with intoxication, CBG could potentially offer a way to encourage eating without the high.

How CBG Differs from THC and CBD:

| Aspect | CBG | THC | CBD |

| Psychoactivity | Non-intoxicating | Psychoactive (causes a high) | Non-intoxicating |

| Receptor Action | Mild affinity for CB1/CB2 | Strong CB1 agonist (brain) | Modulates ECS indirectly |

| Focus of Research | Anti-inflammation, neuroprotection, antibacterial | Euphoria, pain, nausea, appetite | Anxiety, epilepsy, pain |

| Natural Abundance | <1% in most strains | Often 15–30% | Often 10–20% |

Best Ways to Consume CBG

Because CBG is found in low concentrations in most cannabis plants, growers have developed CBG-dominant hemp strains to increase yields. Here’s how it’s typically consumed:

1. Smoking or Vaping

CBG flower can be smoked or vaporized just like traditional cannabis. Vaporizing at lower temps (~126°F or 52°C) may help preserve delicate CBG compounds.

2. Oils and Tinctures

CBG is often extracted and made into tinctures. These allow precise dosing and can be taken sublingually for faster absorption.

3. Capsules or Edibles

CBG is also available in capsule or gummy form. These are convenient but undergo first-pass metabolism, meaning they take longer to kick in.

4. Topicals

CBG is being explored in skin-care products for its potential anti-inflammatory and antibacterial benefits. Applied to the skin, it won’t reach the bloodstream in significant amounts but may help locally.

Safety and Legal Status

Like other cannabinoids derived from hemp (containing <0.3% Delta-9 THC), CBG is federally legal in the United States under the 2018 Farm Bill, though individual state laws vary.

CBG appears to be well-tolerated in studies so far, with no major side effects reported. Still, more clinical research is needed to confirm long-term safety, interactions, and optimal dosing.

Conclusion

CBG stands out as one of the most promising minor cannabinoids, offering unique benefits separate from THC or CBD. As research grows, we may discover even more about its role in supporting inflammation control, neuroprotection, bacterial defense, and overall wellness.

If you’re curious, exploring CBG through flower, tinctures, or blends is a fascinating next step in understanding how cannabis can be tailored to individual needs. As always, consult with a healthcare provider before starting any new supplement routine.

Sources:

General CBG Overview & Endocannabinoid System

Pisanti, Simona, et al. “Cannabinoid receptor signaling in neurodegenerative diseases: from the bench to bedside.” Progress in Neurobiology, vol. 153, 2017, pp. 64–81. Elsevier, doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.03.003.

Link

Anti-Inflammatory / IBD Research

Borrelli, Francesca, et al. “Beneficial effect of the non-psychotropic plant cannabinoid cannabigerol on experimental inflammatory bowel disease.” Biochemical Pharmacology, vol. 85, no. 9, 2013, pp. 1306–1316. Elsevier, doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.01.017.

Link

Neuroprotective Properties

Valdeolivas, Sara, et al. “Neuroprotective properties of cannabigerol in Huntington’s disease: in vivo R6/2 mouse model.” Neurotherapeutics, vol. 12, no. 1, 2015, pp. 185–199. Springer, doi:10.1007/s13311-014-0304-z.

Link

CBG and Glaucoma / Eye Pressure

Colasanti, B. K., et al. “Ocular hypotensive effect of cannabigerol.” Journal of Ocular Pharmacology, vol. 2, no. 4, 1986, pp. 369–375. doi:10.1089/jop.1986.2.369.

Link

Antibacterial / MRSA

Appendino, Giovanni, et al. “Antibacterial cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa: a structure–activity study.” Journal of Natural Products, vol. 71, no. 8, 2008, pp. 1427–1430. ACS, doi:10.1021/np8002673.

Link

Appetite Stimulation

García, Carmen, et al. “Cannabinoid regulation of food intake and impact on food choice.” Current Opinion in Pharmacology, vol. 5, no. 6, 2005, pp. 597–602. Elsevier, doi:10.1016/j.coph.2005.09.011.

Link

Legal Status & Safety

U.S. Congress. Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (2018 Farm Bill), Public Law No: 115-334. 20 Dec. 2018.

Link